I don’t know what something looks like until I draw it.

Georgia O’Keeffe

Think of all the things - large and small - that began as drawings on paper.

As a culture, we are in the midst of a great technological upheaval, and the design profession is being redefined as much as any industry today, with all the implications of the digital revolution still to be played out. But the further I go into this profession, and the further into technology, the more convinced I am that experience with a pencil and paper is fundamental, even primal -

And that is not going to change in our lifetimes.

Here's the thing about drawing -

We don't see the world around us in a flash; we construct our perceptions through a series of darting glances at interesting bits and parts - we see the world initially as a series of 'details' that attract us. At the unconscious level our brain stitches the bits and pieces into a workable whole. We must teach ourselves to see the whole forms, the big picture, consciously - to see the larger composition that the details sit believably within.

In our drawing classes over the next three years we'll draw observationally much of the time - often from the human figure - and this is an invaluable, fantastic exercise, like jogging every week; it is guaranteed to make us better people. But the primary use of drawing for a designer is to draw what's not yet observable, since we, by definition, create things that don't exist yet - our drawings show our collaborators what will be in the future. So our objective while drawing observationally is to help us draw the figure when there's no figure, and the space when the space isn't before us, and the light when it isn't shining.

And we begin by learning to see through methodical observation. Really really really understanding what it is you're looking at.

That this may be intimidating to some is understandable, and maybe you think you can slide by and be a non-drawing designer who manages with computers and assistants to avoid ever picking up a pencil. But It is possible to design and not draw in just the way it's possible to live in France and not speak French - you can manage to get by if people are polite to you and help you, but you're not really living there fully and independently.

One thing I have learned after teaching drawing for a number of years is that everyone - literally everyone - secretly fears in the center of their heart that they don't draw as well as they should. I feel this way, often. That this feeling is universal should give some comfort - you're not at all alone.

And wherever you are in your development is where you are - you will be drawing at a higher lever at the end of your first year through your practice and continual thoughtfulness about drawing, and after three years you will be AMAZING (take a moment to visualize the wonderful artist you will be in three years, how expressive and alive your drawings will be, bursting with ideas and energy). So the first step is not to compare yourself with everyone else - easier said than done, I know, but try. This is all about You advancing from point A to point B in your development as a designer.

Maybe the earliest use of drawing was in drawing maps - using a stick to make lines in the dirt to show where the stream was and where the deers were this morning. And the idea of drawing as mapping is a useful one. You can think of a design drawing - say a costume sketch - as a map for one’s collaborators in the creation and use of the costume. What are the parts, how do they fit together? It’s there in the drawing.

This way of looking at drawing takes aesthetics out of the equation, mostly. One can judge the usefulness of a drawing by how much information it contains as opposed to its level of aesthetic beauty (remembering that aesthetics themselves are information).

If you let it be, it's breathlessly exciting.

Your Mission

Draw something, literally any natural, organic form, like a tree branch or a head of lettuce or a red pepper or a potted bamboo plant - anything you can put on the table in front of you and draw. Let’s go with an organic object rather than something manmade.

Use a pencil (maybe an HB pencil) and a nice piece of paper (perhaps vellum bristol, not lined notebook paper rudely torn from a pad).

Think of the point of the pencil as being the tip of your finger, and each line is your finger moving over the form. Let the drawing go where it will.

Leave out any ’shading.’ Draw to show me what makes this tree branch this particular tree branch. I repeat: no shading. Just your pencil line.

Is there some quality of this object that can’t be conveyed with your line? Add a note somewhere describing the color or texture or something.

Listen to what you think as you draw. Quiet the voice that says 'I don't know what I'm doing. It already looks terrible. There are children better at this than me" - you know that voice. Instead, I want you to concentrate and think, 'All right, this goes Here, and then this line curves like So, then jogs a bit, then connects to that right Here. And this bends out like so - or, better, like So, then it is a bit bumpy, and then smooth." Describe to yourself, forcefully, what everything in the drawing is Doing.

Notice your thoughts, as if from a distance, examining your own reactions. Maybe even note them on the drawing.

I really am asking you to drown out your self-critical voice with the wiser voice that's engaged in the task.

Share you thoughts on the process with me. I’m as interested in your experience as I am the drawing.

By Friday July 15, send me the drawing, as a scan or a digital photo, and your thoughts about it, here:

chrismullerdesign@gmail.com

and I will respond.

We're off and running.

Regards,

Chris

(Note: please put your name in the title of the image, like MyNameDrawing1.jpg, so I won’t be confused about which drawing belongs to who)

Week 1

Week 2

THE LINE

In drawing, the line is the basic tool of the art form as well as its great limitation. It is an abstraction, for true lines seldom appear in the world around us (perhaps veins? the ‘lifeline’ and other lines on our hands? A long straggling hair?) but we use the line to describe edges and changes of plane and changes of color, and if the line is used sensitively and responsively it will convince us that we are seeing an edge or change of plane or change of color.

The line is useful and even exciting in the way it leads our eye along the surface of the paper. But if we’re trying to convey dimension and mass and depth, to give the illusion of form and space, the line must disguise itself.

I like the word ‘responsive,’ especially in describing drawing. I like seeing how an artist has responded to what they are drawing, if they are drawing from life, or how they responded to an imagined image. A line that responds with beautiful expression to a contour, a change in texture, to a subtle or strong bend - that’s what’s interesting to look at, in my mind.

Many people use a wispy line, composed of many short strokes, and sometimes one’s can eye stumbles along a curve described with so many strokes. It feels like someone driving a car by hitting the accelerator for just a short burst that takes the car forward just an inch, over and over. You can just hit the accelerator and go, and drive along the curves and angles with joy and the wind in your hair!

Your Mission

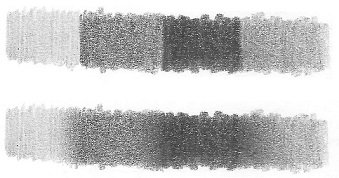

An angular, choppy line feels different than a sinuous, curving line, and both may have a place in different parts of a drawing. Also, lines can be thick or thin, or start thin and become thick and thin out again. A thick strong line may describe a large form and small lines convey details within - or the other way around.

Let’s try this. Just for the sake of this exercise we’ll use three line weights - heavy, medium, and light. You could three different pens, or three different pencils of different softness and hardness.

Let us draw a nice, interesting vegetable - I want to encourage healthy eating habits whenever I can, and we can draw ice cream and candy later - and slice this vegetable in half. Draw this as a still life, and use your heaviest line to describe the silhouette - the overall contour. Use your medium line to describe details within, the major forms revealed. And use your thinnest line for the small details.

How do these lines guide the eye? How do the three relate to each other - where are shapes echoed, where is there contrast? Even think to yourself, ‘This goes here … and this bends this way … and this stops abruptly here …’. We’re trying to bring everything to a conscious level.

What can this method describe, and what elements of the vegetable have to remain undescribed - like color, texture, or even scent and taste. What does the drawing do, what does it not do?

Send to me by Friday July 22, and I’ll tell you what I think!

Give it what time you can. And again, make it enjoyable for yourself.

Henri Matisse, 1941

Marie Cassett, 1890

Picasso, Portrait of Stravinsky, 1921

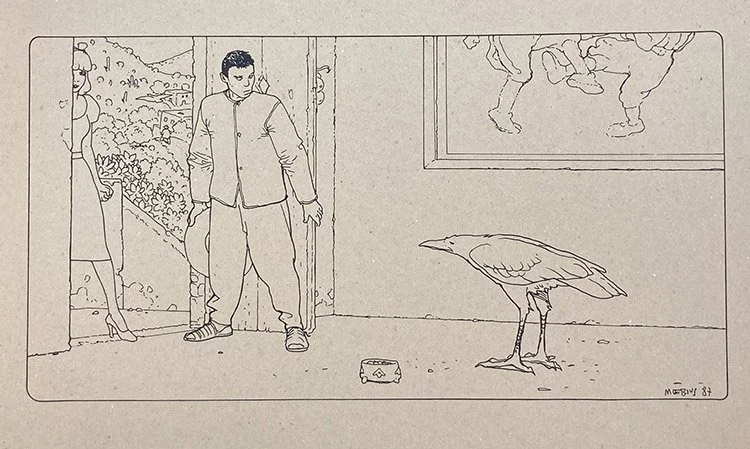

Moebius (Jean Giraud), 1987

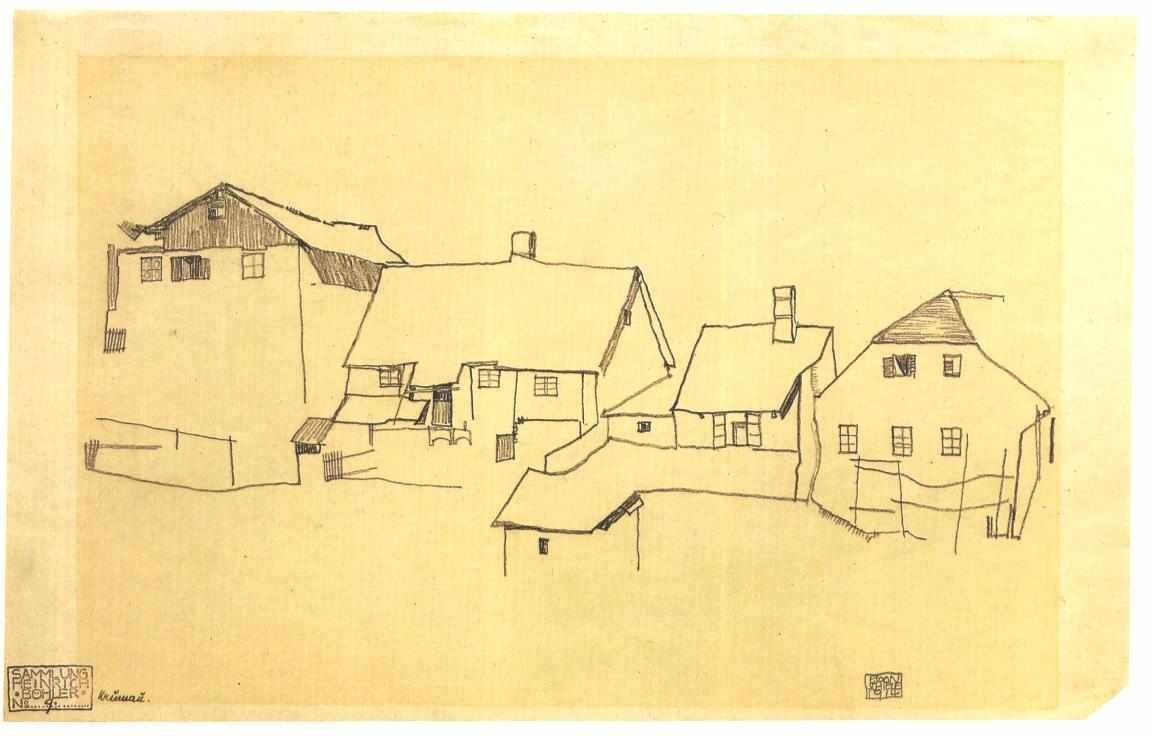

Egon Schiele, 1915

Week 3

Throwing Shade!

Alright, after completely banning shading for 2 weeks, and calling out all of you who tried to sneak some in (I saw that cast shadow …), now we can turn our attention to shading and nothing but.

In the scheme of things, I don’t think ‘shading’ should be separated out from all the other aspects of drawing, as it should be an organic part of seeing a subject coherently.

We see all objects and spaces revealed to us through light, so in essence all things emerge from darkness where a source of light hits them. The math of it all is simple: where an object, plane, or side faces a lit source it is illuminated; where it faces away from the light it is in darkness, and the degree to which an object is at an angle to a light source it will be seen as darker relative to that degree.

And working out the nuances of that takes a lifetime of observation!

Look at these wonderful drawings by Georges Seurat (the Post-Impressionist painter of pointillism fame), done in conte crayon on a rough paper - note the lack of lines at all, and everything scene purely in tone.

You all noted in your line drawings that you could get quite detailed, but at the expense of a sense of light and dark and of color - here Seurat creates a wonderful sense of light and dark, but at the expense of detail.

Something further to think about: note the difference between ‘shading’ and ‘shadow’ - Shading is rendering the darkening of an object as it turns away from the light source; Shadow is the interruption of the light source by an object, where the light continues until hitting another object and surface - in other words, a shadow is the cast shapeof the object that interrupts the light source. To think about later: what different qualities do ‘shading’ and ‘shadow’ have?

You can consider, as you observe and draw, how deep the metaphors of ‘light’ and ‘shadow’ are, and how a simple still life can be a meditation on their interplay.

Your Mission

This takes a little set up. Choose a nice still life subject, some nice object or two, and light them with a single light. Perhaps you can do this in the evening when the changing sunlight doesn’t alter the shadows.

Let’s work on neat and specific shading: as much as possible, pure tones and not scribbly lines. Make shapes. Simplify.

Your pencil tip should be ground down on a piece of scrap paper to create an angled plane that will make lovely values.

We’re not cross hatching here, but using tones that underplay, or hide, individual lines.

If you want to be as much like Seurat as possible, you can use a soft pencil on something like watercolor paper.

As before, you’re making an exploration, discovering as you draw. What you find you find. You won’t get anything wrong. Just draw in the moment, fear of not making a ‘correct’ drawing sent away for the evening.

Play nice music. Tell me what you listen to, purely for my own curiosity.

Send to me by July 29. Have a nice week!

Georges Seurat, ‘The Artist’s Mother,’ 1883

Georges Serait, ‘Café Concert,’ c. 1886

Wayne Thiebaud, ‘Sketchbook Candy Apples and Watermelons,’ 1984

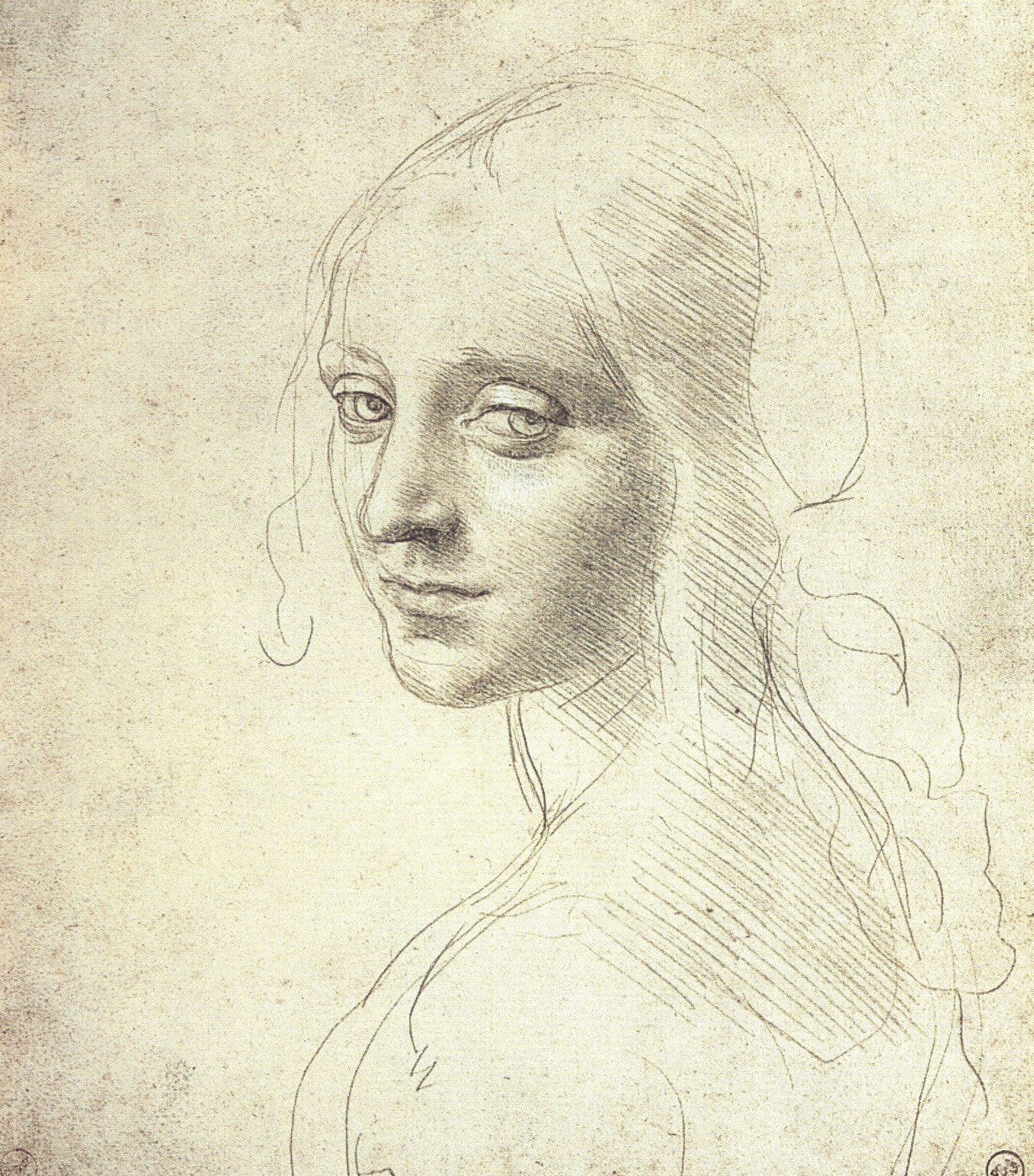

Leonardo Da Vinci, ‘Drawing of a Woman,’1483, silverpoint. Note how Da Vinci seems to slowly evoke the woman’s form with diagonal lines, pulling and pushing the form into and out of the paper’s surface.

Week 4

The Body in Question

As designers we get to become experts on size, measurement, and distance - distance of a light throw, height of a window, the inseam of a leg. We work to deepen our understanding of proportion, the parts to the whole, all the time.

We need a frame of reference to place everything within, and the human body - ourselves - is the obvious starting point. We get to be experts on how we fit into the world around us.

We will look at some proportions of the human figure. It is time to move past the concept of ‘ideal’ proportions which has dogged Western art for centuries - the concept doesn’t have room for all the variations of shape and proportion humanity presents to us. But we can start with ourselves.

Some of you may know different ways of dividing up the body, like drawing a figure 8 heads high. I offer a proportion based on bony landmarks:

Top half of the body, divided in thirds:

Head to collarbone; collarbone to bottom of ribcage; bottom of ribcage to crotch.

Bottom half of the body, divided in half:

Crotch to knees; knees to feet.

It pretty much works.

From this point forth, always note how you measure up to places and things - what is above your eye level and what below; what comes up to your waist, what comes up to your knee; how high can you reach up, how high of the ground are your eyes? You’re a walking measuring device that you can compare to everything else in the world.

Your Mission

Draw a measured self-portrait, head to toe! Show key measurements - height, wingspan, how high your eyes are from the ground. Draw yourself next to a measured object (chair, Rhino, fan, what have you).

If you like you can follow the model of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, and you have 4 legs and 4 arms you’re ahead of the game!

Send to me by Friday August 5, and I will praise your effort.

Onwards!

Week 5

The Fabric of Space and Time

Have you looked at the drawings of the great masters of the past or at amazing contemporary artists and felt like they all had some secret understanding that, despite art classes and hours of smudgy charcoal, no one had ever told you?

You're right, they did all have an intrinsic idea behind their work which I am now going to reveal to you, before you've even started class, and you can all thank me later.

In the seminal book 'The Natural Way to Draw,' the great teacher Kimon Nicolaides says it this way:

We don't draw what something looks like; we draw what it is doing.

We draw the action, the forces and gestures of things. Gravity pulling down, energy thrusting up, action twisting and turning.

We draw the verb and not the noun.

An excellent subject to apply this to is fabric, an active fluid material that shows the effects of force and action even in repose.

Every single designer needs to understand the qualities of fabric, what it does and why, and costume designers become complete experts on every seam and weave and thread. In the kit of symbols we learn to draw with, however, we don't really have workable marks for drawing fabric

We must always draw fabric by drawing the pull of gravity, what keeps the cloth from falling to the ground, and how does it twist and fold around forms. The dress, for example, that hangs from the shoulders and gathers across the chest and cascades down the back - it really helps to think in terms of active verbs that give life and energy to the forms of fabric. The dress is not just There - so much is happening!

Think of verbs that can describe fabric; here's 15 off the top of my head:

Fall

Cascade

Drape

Spiral

Flow

Buckle

Stretch

Burst

Tear

Gather

Bunch

Pucker

Pinch

Drop

Twist

George Bridgman, teaching at the Art Student's League a hundred years ago, broke down the different effects of fabric into the following five categories, as you can see on the right:

Your Mission

Take a piece of fabric, drape it over a chair, and draw it in pencil. Simple as that!

It may be a dress, a sheet, a towel, 2 yards of China silk - it's up to you. It should be a solid color without any pattern, and it probably should be a lighter tone for simplicity's sake. Convey the sense of the fabric's fall to the ground while being impeded by the hard form of the chair. Use shading simply and clearly. Use line weight to make the overall form clear, and don't let the lines of folds and wrinkles overwhelm the drawing - big forms first, details within.

If you like you can draw on toned paper like I did with black and white media - I was drawing in charcoal and chalk.

Send it to me by Friday, August 12.

Convey the gesture, the action, the tension between what the fabric hangs from or drapes over and the powerful pull of gravity!

Here’s the key: talk to yourself as you draw: ‘now this is jamming into this other fold, but then it falls over the edge and cascades down to the floor, where it crumples and lays there like a sleeping cat.’ Keep your thoughts active and drown out your doubts and the rest of the world!

And show me that rather than just doing an exercise, you are opening yourself to the miracle of actuality before your very eyes, the joy of perception! As William Blake said, all movements and all sights contain the seed of ecstasy!

Week 6

Reporting

We spoke at the beginning about using drawing to understand what we’re seeing, as Georgia O’Keeffe says in the quote at the beginning of our blog here. One of the most basic uses of drawing is jotting down visual notes for later use - like JMW Turner’s scribbled sketches that he somehow turned into large colorful oil paintings later in the studio (the sketch apparently assigns numbers to different colors).

Yes yes, you’re a modern person and you can just as easily take a picture with your iPhone, but you haven’t really learned anything in the process. And as we earlier defined what makes something a design sketch as distinct from other types of drawings, with a sketch you can make notes, recording details and your own thoughts and impressions, as the painter Edward Hopper did here, recording light and color ideas.

Recording your encounters and reactions throughout the day is extremely useful, a way of engaging with the world and your time, briefly capturing the never ending flow of moments that carry us along. And the drawings you make and the notes you take are 100% yours, not filtered through anyone else’s sensibility - the very act of reporting in your sketchbook is a way of defining yourself.

Your Mission

This is a transitional moment for everyone as you enter back to school, and many of you are traveling with periods of inactivity as you wait and wait in airport terminals and the like - a perfect time to take a moment and record what’s around you, what attracts your attention, and what thoughts are in your head.

Look around, draw some things, record some thoughts! Don’t think about beautiful drawings, don’t think about what use your sketches could be put to - just draw some things or people or spaces that you are experiencing now.

My secret agenda is for you to begin a habit that will last, and run parallel to your work and class, but is just yours.

Send to me by Friday August 19. Enjoy!

Week 7

Marching Orders

What would it be like to see like Rembrandt - to sense the gesture in all things, looking through the squalor and ugliness and finding a deeper, hard beauty in all that: what was that like? Can we let him suggest to us the penetrating gaze, the love of everything alive and being and moving?

Even if you’re listening to pounding music in headphones and everything is lit by street lights and neon signs and the subway rumbles underneath you?

Is Rembrandt’s gaze - 350 years old, pre-industrial, pre-electric, pre-mass-media - unrecoverable, anachronistic, irrelevant?

I ask myself this all the time.

There’s a saying in Torah study that if Moses were to come to a temple today he wouldn’t understand Torah, for he has missed out on 2500 years of commentary.

You have the amazing good luck to be a designer of today, right now.

When I went to NYU, my teachers were men and women of the theater of the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s. They taught about designing for a world that economically, technically and culturally doesn’t exist anymore - and yet their deeper lessons about design and life go through my mind every day. Even if I turn their lessons on their heads.

For the next three years, remember this - keep it lodged in some protected part of your mind: It’s going to feel at times that we’re making you draw, see, and design our way, in some official, approved manner. But it’s really about leaping over and flying beyond. We’re here to help you surpass us, and to work in a world that no one knows yet is possible.

Camus said that no graduation ceremony is complete until the students consume the faculty.

I’ve been doing this design stuff professionally for over 30 years and I’m good and smart and you should listen to everything I say - and I want you take everything I have, like a thief in the night, and twist it for your own ends.

The Baoulé people of the Côte d'Ivoire say that art is dangerous if you just look at it; it is healing if you absorb it with your whole body.

Your Mission

Be astonishing.

Have a great year!